Structuring the Course: How do I put it all together and explain it to my students?

A well-organized course provides a clear path for students to progress. By providing structure and clear, welcoming instructions and information students will be more comfortable and confident and will ask fewer logistical questions.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, we hope you will be able to:

- organize your course using folders

- use the course entry point for the home page and/or a "Getting Started with the Course" content area to welcome and orient your students

- write a readable, accessible syllabus that includes the information necessary for online students

Table of Contents

- Structuring your Online Course

- Structuring the Course: Communicating Your Plan and Intentions

- Structuring the Course: Organizing the Syllabi for Online Courses

- Structuring the Course: Writing a Good Syllabus

- Structuring the Course: Resources for Building the Course

Structuring Your Online Course

How do I put this all together?

If you're to the putting it together stage we're going to presume you already have the following:

- Clear and measurable learning outcomes

- Assessments that can show to what extent your students have met the learning outcomes

- Activities and other active learning strategies to allow students to practice doing what you describe in the learning outcomes

- Content that provides sufficient information, explanation, and demonstration, in both written and visual form, for students to successfully reach the learning outcomes

Consistency is the key

While there are many different ways to organize your course, once you choose your strategy the best thing you can do for your students is to implement it as consistently as possible. Like in-person students who get in the habit of going to class at the same time and the same place every week, online students need to form those same habits to maintain consistent performance across the semester. Making sure that assignments are always due on the same day of the week and the folders always begin on the same day of the week goes a long way to providing structure.

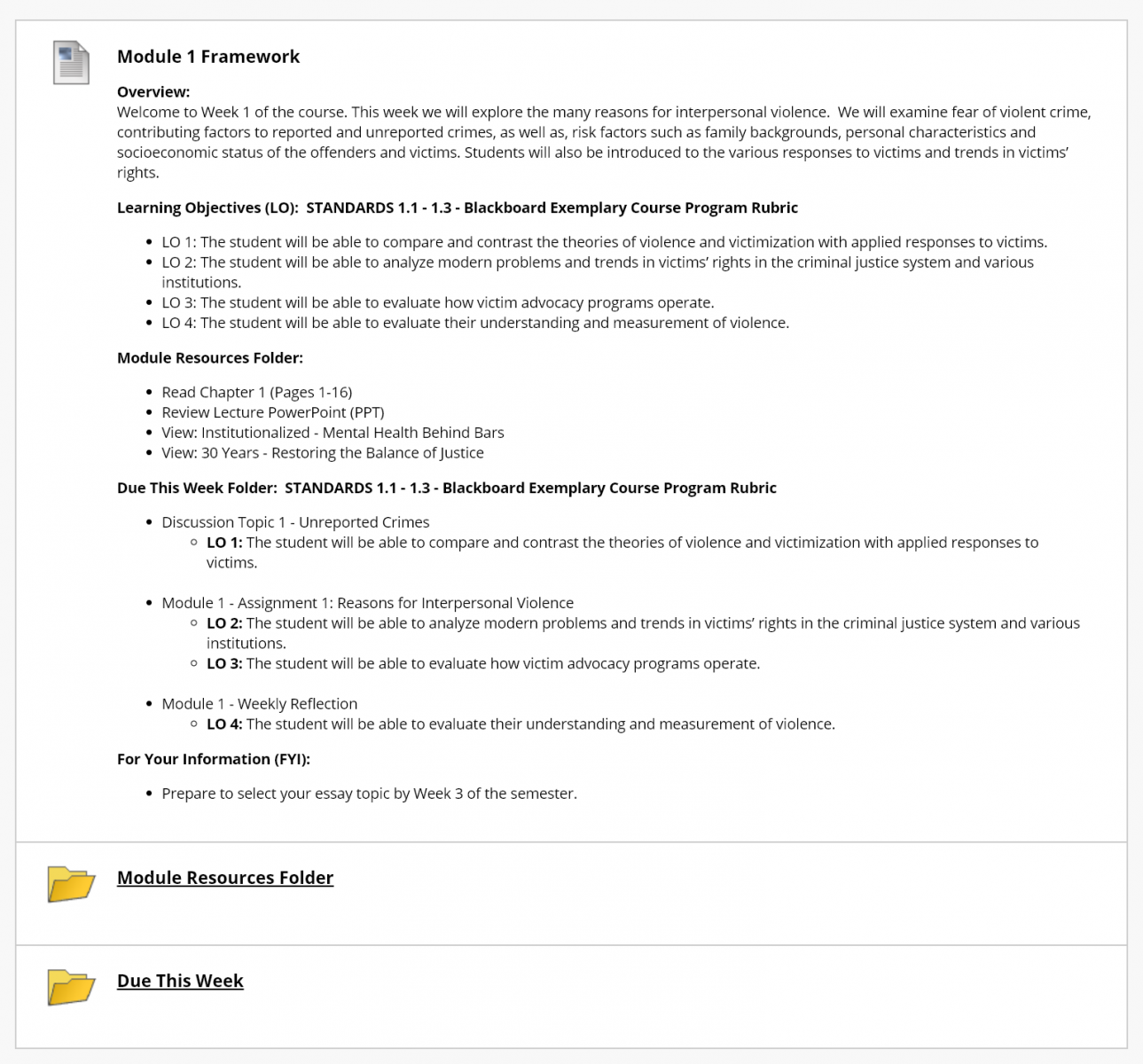

Students also benefit from consistently having an overview of each folder describing what they are to do and learn. By placing an overview (either written or on video) at the beginning of each folder as an advance organizer, students are better prepared to complete it. The overview should also include a list of reading (identifying chapters from books or linking to digital resources) and brief assignment descriptions or links to Assignments, Discussions, or Quizzes where the full descriptions are. Some faculty members like to put the overview description or video on one content area and then readings and resources on a subsequent content area and then have assignments and activities follow individually in the folder. Either way is good as long as you pick one approach and use it consistently.

Even if you are working from a strong constructivist frame, when putting your course together make sure to keep in mind the scaffolding provided by the three phases of direct instruction (Links to an external site.):

- I Do: How are you modeling and explaining new material and the ways in which new material connects to previous concepts? See the Multimedia module for ideas on presenting these think-alouds and walkthroughs.

- We Do: How are you guiding and coaching the learning process? Providing prompt and actionable feedback is one way but preemptive checks on understanding and formative feedback can help support learners before misunderstandings are documented in assignments.

- You Do: How are you providing independent practice? Keep in mind, independent doesn't have to mean alone. Group work can provide collaborative practice independent of the instructor.

The long and the short of a Folder

In Blackboard, you can make course organization and navigation easier for yourself and your students. It is the place where you organize your activities, content, and assessments in the order in which you want your students to progress through them. Having all instructions, content, activities, and assignments in folders avoids the problem of telling students to "go there and do this" and then "go somewhere else and do that".

A very important benefit of the folders is that, by organizing all your content, assignments, quizzes/tests, discussions, etc. in folders, you can hide the Assignments, Quizzes, Discussions, and Files from student view. This gives students one and only one place to look for everything. That means fewer "where is ____?" questions for you and less frustration for your students.

The more doors students have to the same items, the more confusing it is for them and the harder it is to be sure they are in the right place. This is because in Blackboard, all of the other tools organize these items differently than you do in folders.

There are two schools of thought about how to organize items in folders: the long version where every item is a separate part in the folders including links and readings as well as activities and assignments and; the short version where each folder contains an overview Content Item that includes a list of the books or chapters for the topic as well as links to other items the students are to read, watch, and explore.

Short Version:

Long Version:

.png)

As you can see, making each item separate elements can significantly increase the length of the content and the long version can appear overwhelming to students and reduce motivation. On the other hand, instructors are concerned that students skip over readings and don't explore links unless they are required to progress through them one at a time.

Structuring the Course: Communicating Your Plan and Intentions

Getting Started with the Course

For a student, the beginning of a new semester can be both exciting to start fresh and frightening to not know what you're getting yourself into. Students who haven't taken an online course before can be overwhelmed going into a course site with no direction or explanation. Even if they have taken an online course before, there is no way of knowing how their previous instructor organized that course and what the student's experience of that course was. Therefore, it's still important to provide sufficient instructions, additional information, and begin to calibrate student expectations of the course by modeling appropriate behavior.

Using the entry point (home page)

When students log in to your course for the first time they need to see something that orients them to where they are and explicitly communicates what they are to do in a friendly and welcoming manner. Even though you have several options for the course home page, it is always recommended to set your course home page to the announcements tool that you have created (Links to an external site.). Starting new students on a syllabus at the home page or a week/module list isn't nearly as welcoming as a home page with important course announcements that can include your contact information, a picture of you, a personal welcome, and instructions on what to do first.

It would be best if the course home page were set to the announcements tool in your Blackboard course.

Since your students come to your class with a wide variety of previous online learning experiences and expectations, communicating your expectations for your students from the beginning is a good way to set the tone for the course and course communication. Some faculty prefer to write out course expectations and only do a personal introduction video. Other faculty members like to do a brief video providing an overview of the course like the one below and post it on the home page or on a separate "Getting Started with the Course" content area. Here are two examples of different points in the production quality and creativity range.

Transcript - Example Course Introduction: Environmental Public Health (File can also be downloaded under Attachments at the bottom of this article)

Transcript for Zombie Infections Course (File can also be downloaded under Attachments at the bottom of this article)

Using a "Getting Started with the Course" Content Area

A Welcome Content Area called something along the lines of "Getting Started with the Course." In addition to those topics, there are a few other examples of items that could go on that home page as well. Here are some sections you can take, paste into your course, and customize.

-

Netiquette:

One thing to always keep in mind when taking any online course is that the others with which you interact throughout the semester - including me, your instructor - are human beings. The first rule of netiquette (Links to an external site.) is to "remember the human" when you are communicating with me or with your peers. The second rule is to "adhere to the same standards of behavior online that you follow in real life." It's not likely that students would yell at, mock, or belittle another student in a face-to-face class but the feelings of anonymity that some people have when they are online can lead to those sorts of behaviors. Clearly stating that they are not acceptable in an online class may seem unnecessary but stating it upfront and linking it to the Student Code of Conduct can provide a more direct route to correct

Please take a few minutes and review all the Core Rules of Netiquette (Links to an external site.) and make sure you have a profile picture added to Blackboard (instructions on Uploading a Blackboard Avatar) before beginning the class.

-

Course Structure:

This online course is divided into X Weeks/Modules as listed in the Syllabus.

Each Week/Module is X weeks long. They normally include:

- material for you to read, watch, and explore;

- an activity such as a discussion where you interact with your classmates in a small group, and

- a graded assignment to allow you to work with the concepts and resources (sometimes individually, sometimes together).

If the content areas are not all visible at the beginning of the semester state that they are not available and when new content will be released (at least two weeks in advance of the week/module start date).

-

Feedback Expectations:

I will aim to provide you with feedback on each assignment within X days. Make sure to check your instructor feedback when you receive a notification that something has been graded.

If you are using videoconferencing at any point in the class it's a good idea to include asynchronous video orientation in the first two weeks. It gives students a chance to test out their video equipment and gives you an opportunity to address any questions or concerns they might have. If you would rather not have a synchronous orientation, having students post a video introduction of themselves also provides proof of their video conferencing ability.

In addition to the course entry point and a getting started content area, you also communicate your plan and intentions in your syllabus, which we will be thinking about on the next page.

Structuring the Course: Organizing Syllabi for Online Courses

Syllabus Basics

A syllabus is both a map of your course and an agreement between you and your students. It's a resource that you will likely refer students to throughout the course. Having an organized, approachable, and accessible syllabus helps to set a positive tone for the course and support students' confidence in you as the instructor. According to backward design, writing the syllabus is one of the last things you do because, until you have worked through your outcomes, assessments, activities, and content, you wouldn't have the information that you need to write one. You are basically translating your course map into a syllabus at the end. If you made a visual course map you may want to include that in your syllabus as well.

What is different about a syllabus for an online class?

An online course syllabus is generally similar to a well-structured traditional syllabus in many ways. The differences center on the need for it to be very clearly written, well organized, readable, and complete. Unless you are doing an in-person or synchronous video orientation there won’t be easy opportunities to talk through confusing points or clarify instructions or explanations. The syllabus needs to convey the necessary information in a way that students can understand.

Research into syllabus construction and the influence of the syllabus on student motivation and retention has influenced growing popularity of a learning-centered syllabus (in contrast to a coverage-centered syllabus). This also reflects the Significant Learning process by Fink (Links to an external site.) as we mentioned in the Outcomes Module. This is an especially useful form for online students who may have no interaction with an instructor in the first few weeks of class. While still containing much of the standard information, a learning-centered syllabus also communicates enthusiasm, mutual accountability, and a belief in students' learning potential, as well as respectfully socializing them to the roles and norms of the class (Habanek, 2005; Sulik & Keys, 2014).

Palmer, Bach, and Streifer (2014) developed and validated a rubric for learning-focused syllabi review (Links to an external site.) reflecting the importance of learning outcomes and alignment as well as Fink's Significant Learning taxonomy. Their rubric criteria include items such as:

- well organized and easy to navigate

- a positive, respectful, and inviting tone

- directly addresses the student as a competent, engaged learner

- indicates a learning environment that fosters positive motivation (see teaching approach section below)

- clearly communicates high expectations and projects confidence that students can meet them through hard work

Expectations and Responsibilities

As noted in the rubric, in an online course it is important to define expectations and responsibilities up front as much as possible. Online there are fewer opportunities for peer pressure to encourage disengaged students to participate. Making sure participation expectations, as well as other expectations such as writing quality, citation format, etc., is quite helpful to both your students and to you as the semester progresses. While spelling out these sorts of expectations in the syllabus may seem odd at first, you will appreciate taking the time to do so - and doing so in a positive, encouraging manner - as you refer students back to that pre-written section.

Complete Syllabus

Having a complete syllabus at the beginning of the course is often much more important for online students than for on-campus students. On-campus students who physically see you every week tend to have a higher tolerance for ambiguity so it is easier for instructors to make decisions about the course as they go along. Changing the focus of a week, swapping out an assignment, replacing readings and resources are all easier for students to manage in an on-campus course. Online students who are balancing schoolwork with jobs and families are less amenable to change and lack of evidence of clear planning tends to make them anxious when they don't feel a personal connection with the instructor. Lack of visible proof that the course is fully planned can be unsettling - especially to online students that have had the experience of being in a course that was only built a week or two in advance.

Sections of an online course syllabus

As you have seen over your time as a student and an instructor, there are some standard items that are on most syllabi (Links to an external site.). Instructor contact information, required textbooks, course grading scale, and university, school, and department policies are almost universally included. Other sections recommended to make your syllabus complete, and sufficiently detailed include:

- measurable learning outcomes which are then referenced throughout the course

- brief week/module descriptions - these are especially important if your week/modules are not all open to students at the beginning of the semester

- technology requirements such as needing a headset with microphone, a webcam, or specialized software, if applicable

- a clear statement about types of academic misconduct, their consequences, and the Code of Student Rights, Responsibilities, and Conduct.

On the other hand, there are also some sections you may include on your on-campus syllabus that are not needed in an online class because there are other places where they should be. For example, some instructors automatically put a section in the syllabus for detailed assignment instructions because in the on-campus class the syllabus may be the only piece of paper students keep. In an online class, the detailed assignment instructions should be kept with the Blackboard Assignment, Discussion, or Quiz and only a brief overview of the assignments needs to go in the syllabus.

Faculty also often write up a schedule and include it as part of the syllabus. In Blackboard, as you put due dates in published Assignments, Discussions, and Quizzes, they are automatically added to both the course Calendar and at the bottom of the Syllabus Tool. When you change a date in one place it is automatically updated everywhere else in the course where you would have entered it in a due date field. Wherever you type a due date in a text box or a document, if you change it you have to manually find every instance where you typed it in and change it yourself. By using these automatic schedule tools you know everything will be consistent and students will not see different due dates for the same assignment.

Other important items to pay attention to in a syllabus for an online course include:

- When and how are you available to your students: Many instructors find that holding online open office hours is less effective than asking students to request a meeting and finding a mutually acceptable time. It's also helpful to have options for how to meet that include both phone and video. Providing more than one option for contacting you, as well as stating how quickly you will respond to requests for a meeting provides a signal to students that you are accessible to them should they have a question or a concern.

- How the time zone of the course affects deadlines and other communication: If your assignments are due at midnight students need to understand if that means only midnight in the eastern time zone and 11pm or 10pm or earlier in their time zone or if it means midnight in their respective time zone. Clarifying time zones for synchronous activities is also critical as time differences are not something most people think about on a regular basis.

- How the course progresses through the semester: Many students come to online courses with the expectation that it will work like a correspondence course - they can do what they want, when they want. The fact that there are deadlines, interaction, and potentially, group work involved can be a surprise. Making sure they understand the pace of the course from the beginning helps to set realistic expectations for student participation. If you have 1-week/module with more than one regularly occurring due date (for example, initial discussion posts are due every Friday and quizzes are due every Sunday) it is critical for them to understand the pace and rhythm in that first week.

Important Sections for Student Support

There are also some specific sections that should be included on every syllabus that you may not automatically add.

- Disability Accommodations

- Technology Support

- Academic and Student Support

Accommodations for Students with Disabilities

Every attempt will be made to accommodate qualified students with disabilities (e.g. mental health, learning, chronic health, physical, hearing, vision, neurological, etc.) You must have established your eligibility for support services through the appropriate office that services students with disabilities. Note that services are confidential, may take time to put into place, and are not retroactive. Captions and alternate media for print materials may take three or more weeks to get produced. Please contact your campus adaptive educational services office as soon as possible if accommodations are needed.

Technology Accessibility Information

For accessibility information for persons using adaptive technology with Blackboard, please visit Blackboard Product Accessibility.

For each external tool you are using you also need to provide a link to the accessibility information for that tool.

Provide detailed information on contacting your technology support services including their hours, phone numbers, email, and if they have it, live chat information.

The Academic Support and Student Support sections are recommend in cases where these services are realistically accessible and useful to online students. Availability of online academic support on each campus will vary. If your campus only provides some support service to on-campus students it can be helpful to let these offices and centers know that you have online students with additional needs for support services.

The following are suggested items to include in each section that you would customize to your campus.

Academic Support Services

Here you would list any academic support services available to online students on your campus including how to contact the offices providing the service. If there is a specific person they need to ask for please include that information as well.

Student Support Services

Here you would list any student support services available to online students on your campus including how to contact the offices providing the service. If there is a specific person they need to ask for please include that information as well. These services can include campus-wide services such as:

- Dean of Students office

- Ombudsperson

- Academic and Career Advising

- Mental health services including coping with academic anxiety

- Policies regarding attendance, withdrawals, conduct, and religious holidays

And also any student services contact information for your school or program.

Structuring the Course: Writing a Good Syllabus

What About a Graphic Syllabus?

You may have heard of Linda Nilson's book The Graphic Syllabus and the Outcomes Map (Links to an external site.) which recommends supplementing a text-based syllabus with graphics showing the structure and organization of the course and its learning outcomes. Providing a graphic organizer is also recommended as a good practice in Universal Design for Learning (Links to an external site.) as a method for visualizing the connections between the outcomes and the course content, activities, and assessments. Clearly aligning outcomes with assessments, activities, and content are critical standards in Quality Matters and it is easy to show that alignment through a diagram, infographic, or flowchart. Keep in mind that images should not replace listing the outcomes and weeks/modules in text - they provide an alternative way of seeing the structure of the course.

The course map from Course Planning with Backward Design is an example of an organizational graphic that you could share with your students.

.jpg)

If you are thinking about creating an infographic-style syllabus (Links to an external site.), it is a good idea to keep a plain, non-graphical version that contains any boilerplate/policy language required in your syllabus which you would want to omit from an infographic and also for accessibility purposes. If you are required to use a standardized syllabus consider using a graphical version as a "course overview" document instead of an actual syllabus. If you are considering using additional graphics in formatting to gain attention and promote motivation you'll also want to make sure that your syllabus is accessible.

Writing an approachable syllabus

Layout

The syllabus often sets the tone for the course. Making sure the syllabus is readable, uncluttered, and accessible is a good place to start. If you are providing the syllabus in a PDF or Word document there are some easy things you can do to improve readability and encourage students to actually read the entire document. Participants in Motameni, Rice, and LaRosa's (2015) study indicated that "the more visually separated and accentuated a syllabus is the more students see it as most usable. They want a syllabus that is more visual than textual and more structured with separations than with block text: (p. 83). Since you are not printing and stapling these syllabi or working with a limited printing allotment there is no longer a reason to use a small font, reduced line spacing, small margins, and no white space. For example, the following image shows the difference in readability between single-spaced 10 point Calibri and 1.15 spaced 11 point Calibri.

Tone

Whether your syllabus is in a Word or PDF document or directly in the Blackboard Syllabus tool, writing in second person form rather than third person, academic-style form will make it more approachable. This is true not just in the syllabus but also when describing your activities, assignments, concepts, and evaluation criteria. Using "you" and "your," "me," "we," and "us" helps students to think about the course as an active connection between people and not as a separate, inanimate object. When in doubt, run your text through a Readability Checker (Links to an external site.). You may also find the section on Writing for the Ear in the Multimedia Module helpful. (Scroll down toward the bottom of the page.)

Teaching Approach

In addition to a personal introduction and a course introduction many faculty like to provide a brief teaching philosophy or teaching style statement in their syllabus or introductory materials. If you have one or are working on one for promotion and tenure you already have a starting point. Student-facing teaching philosophy statements should be written in the first person to feel friendly and welcoming. Following is an example from IUB School of Education faculty member Jessica Nina-Lester for her graduate-level qualitative research methods course.

My Approach/Commitment:

In this course, my primary goal is to establish a safe and inclusive environment that will support your learning. Throughout the semester, I invite your questions and critiques, desiring thoughtful dialogue to be central to our learning experience. In this course, we will work to understand a variety of positions and practices associated with the qualitative inquiry process, pushing one another to question taken-for-granted beliefs and assumptions.

Throughout the course, we will remind each other that there is not “one right” way to carry out a qualitative research study. Rather, there are many theoretical and methodological positions from which to work when considering qualitative research. As such, we will work to understand a variety of positions. This does not mean that you may not disagree with one another or with me about these varied perspectives and approaches. Yet, in order to facilitate our learning environment, we will each work to cultivate a classroom space that generates respectful, thoughtful, and empathetic understanding. What we come to learn is a shared experience; thus, we will all work to cultivate a community of learners.

In our learning community, I will position myself as a co-learner, as well as a teacher. Hence, if I am teaching and you are not learning, then I am not teaching. Please let me know! Throughout the semester, I welcome your feedback and will encourage your participation in an informal mid semester evaluation. In addition, throughout the semester, you can expect feedback from me, with this feedback designed to support your growth as a qualitative researcher.

Structuring the Course: Resources for Building the Course

Additional Information

Syllabus Basics (Links to an external site.) from the IUB Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

Palmer, Bach, and Streifer's Rubric for Syllabus Review

References

Habanek, D.V. (2005). An examination of the integrity of the syllabus, College Teaching, 53(2), 62-64. doi: 10.3200/CTCH.53.2.62-64

Motameni, R., Rice, W., & LaRosa, P. (2015). Taking or not taking a class: Students’ perceived physiognomies associated with syllabi. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 7(1). 78-92.

Palmer, M. S., Bach, D. J. and Streifer, A. C. (2014), Measuring the Promise: A Learning-Focused Syllabus Rubric. To Improve the Academy, 33, 14–36. doi: 10.1002/tia2.20004

Sulic, G. & Keys, J. (2014). “Many students really do not yet know how to behave!”: The syllabus as a tool for socialization. Teaching Sociology, 42(2), 151-160. doi: 10.1177/0092055X13513243