|

Article ID: 578

Last updated: 29 Aug, 2025

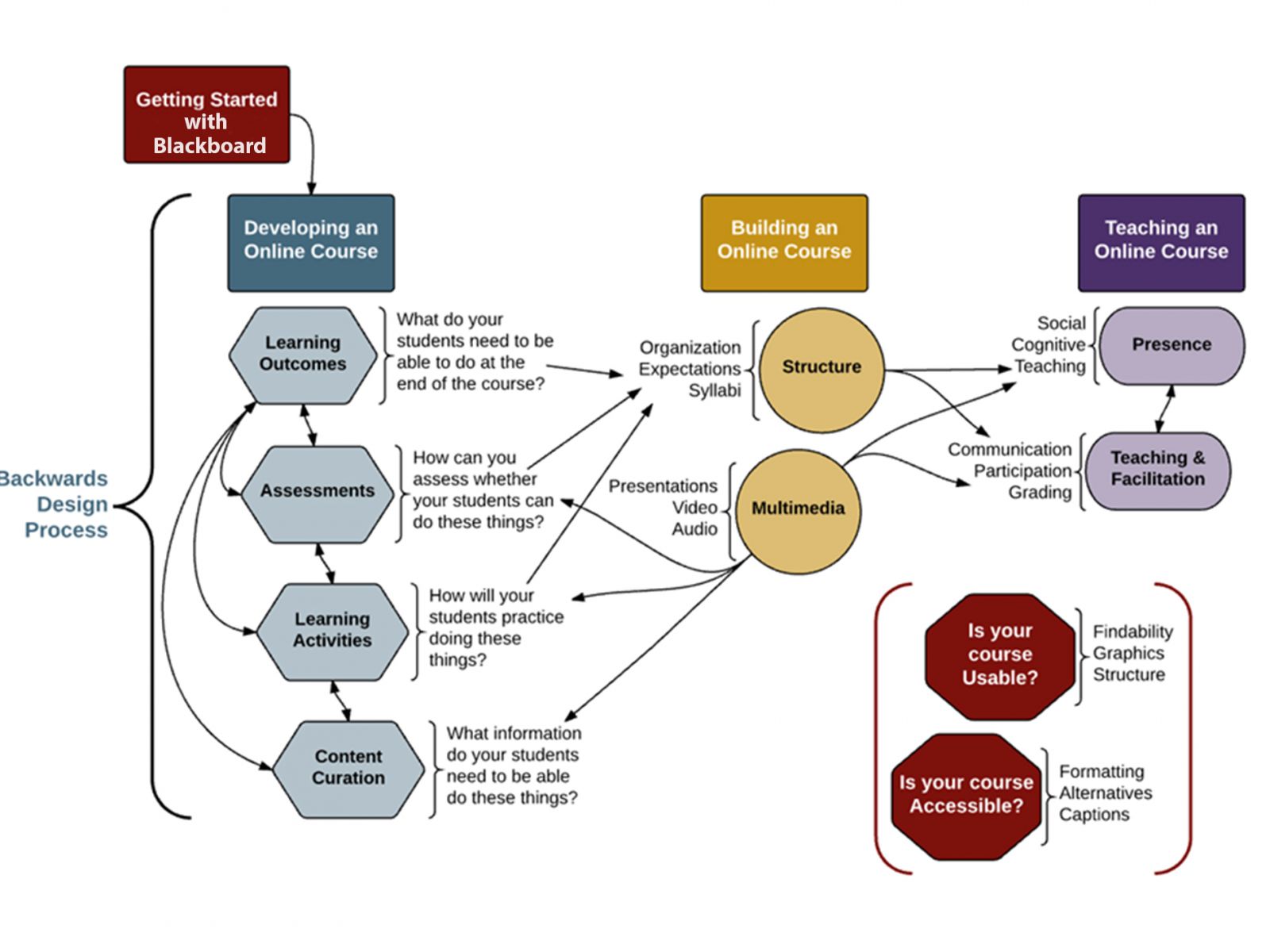

Designing an online course: Where do I start?You may have heard the recommendation to start with the end in mind - the desired learning outcomes for you students. While that's a very valid recommendation, there is more to the process than just having a solid starting point. Learning ObjectivesIn this module, we describe Backward Design as a model for developing or revising online courses to improve validity, dependability, and clarity. We also discuss the first aspect of Backward Design -- learning outcomes. By the end of this module, we hope you will be able to:

Table of Contents

The Makeup of an Online CourseFlexibility: Feedback: Resources:

Communication:

IMPORTANT: Please note within the following modules there will be tool links to software that will be recommended but not supported by ECSU. How are Online Classes Different?If you're new to online teaching and learning, you may be wondering what it's all about. Often faculty have ideas about online classes based on what they have heard from colleagues here at ECSU or at other schools. What do you think about online classes? Transcript of Presentation - What do you think about online classes? (File can also be downloaded under Attachments at the bottom of this article) and HTML View of Presentation Additional misconceptions about online classes include:

Experienced voicesExperienced online instructors uncover their misconceptions over time. In an article in the magazine eLearn, Michelle Everson, a statistics instructor, shares 10 things that she learned about teaching online over the course of 5 years. While everything she shares is insightful, a few points below highlight the dissonance that some new online instructors can feel.

Other commonly experienced differences include

Online Teaching Readiness SurveyAssess your Readiness to Teach OnlineTeaching an online class requires additional skills that you may not normally use when teaching in-person classes. The survey from the link below will let you check your technology, pedagogy, and organizational skills and attitudes related to teaching online. Course Planning with Backward DesignWhat is Backward Design?The Teaching Online Series is designed based on the principles of backward design, a very useful model for designing courses for both online and face-to-face settings. Wiggens and McTighe, in their book Understanding by Design (2nd Ed., 2005), describe the three steps of backward design.

Dee Fink (2013) describes the steps of backward design as making three key sets of decisions:

Alignment (Wiggens and McTighe) or integration (Fink) of desired learning outcomes, assessments, and teaching and learning activities provides consistency for students and supports more accurate construction of course concepts. It's about beginning with the end in mind. Starting with desired learning outcomes, clearly stated in measurable terms, and working backwards through assessment activities, teaching and learning activities, and content delivery. In the following video, a University of Wisconsin faculty member describes how they are using the backward design process to improve courses. Transcript on Educational Innovation (File can also be downloaded under Attachments at the bottom of this article) Prioritizing and OrganizingOnce you have a list of desired learning outcomes for your students you may see that you have more than is practical in a single class. This is quite common for outcomes related to content coverage. Fink (2013) identifies the heart of the issue as designing a "content-centered" course versus a "learning-centered" course. A content-centered course is what everyone is used to - you were a student in them and you likely teach them as well. They start with a list of topics (not uncommonly based on textbook chapters) and work through them over the semester focusing on coverage. Alternatively, a learning-centered course begins with the answer to the question "What can and should students learn in relation to this subject?" and then move forward to organize activities, assessments, and content presentation in a way that supports that learning. By starting from a learning-centered approach, it is easier to prioritize these content-oriented learning outcomes into three groups: the critical, the important-but-not-critical, and the nice-to-know. As you prioritize you will normally see a structure emerging that may not be in the same order or with the same emphasis as before. You will also likely see that there is not enough time to include all of the learning outcomes you have identified. Asking yourself questions like the following can help you sort and prioritize.

Once you have grouped and prioritized your outcomes you'll need to think about how to order them in the course. When you're doing this it's a very good time to also explicitly call out how the different concepts link together. These are the first steps to creating a course map. If you like to outline, you might find a table-style course map (doc, 17k) (File can also be downloaded under Attachments at the bottom of this article) useful. As shown on the table, in addition to the following section on Learning Outcomes, the Assessments, Learning Activities, and Content areas will also include prompts to work on sections of your course map. If you would like to see your course map graphically, Popplet (Links to an external site.) and Lucid Chart (Links to an external site.) provide free concept/mind-mapping tools. Below is an example using Lucid Chart to create a course map of the content for this course. A full map would also include the actual activities and assessments in context.

Writing Good Learning OutcomesWhat are Learning Outcomes?Learning outcomes guide your course design. They are the destinations on your course map. Once you know where you're going, the other questions, "How will I know when students got there?" and "What can I do to help them get there?" become much easier to answer. They are the formal statements describing what students are expected to learn in a course, whether for a classroom course or online. In short, they state where you want students to go (how they get there is the subject of later units). If you think of your course map as an actual map - outcomes are your destinations. One of the major challenges of teaching online is that everything has to be more explicit than in a face-to-face course because the usual channels (your tone of voice, repeated vocal reminders, informal conversations before and after class) are absent. Online, learning outcomes express your expectations to your students. They are (hopefully) clear messages that help students know what you expect from them and what they should spend their time practicing and studying. Learning outcomes focus on specific knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs that you expect your students to learn, develop, or master (Suskie, 2004). They describe both what you want students to know AND be able to do at the end of the course. If you've not thought about learning outcomes from the perspective of what students should be able to know and do before, Angelo and Cross' Teaching Goals Inventory (Links to an external site.) may be of help. Learning outcomes need to specify student actions that are observable and measurable. That way they can be assessed in an objective manner. "Students will appreciate the beauty of impressionist paintings" isn't an effective learning outcome because it's not measurable. On the other hand, "students can identify impressionist paintings and accurately describe criteria for classifying paintings in the impressionist style" is a learning outcome because you can observe and measure the students identifying impressionist paintings and describing criteria. In addition to being observable and measurable, learning outcome statements have to focus on student action. They are about students showing what they have learned, not about the instructor describing how they are teaching. For example, "The students can accurately describe the process of photosynthesis" is a learning outcome while "I will show a PowerPoint presentation on photosynthesis and give the students a quiz" is not. Usage of the terms learning outcomes and learning objectives can vary considerably depending on the author; however, for purposes of this course, you may consider them synonymous (for consistency, we will be using learning outcomes to reinforce the importance of observable behaviors). ActivityThe following Quizlet provides some potential learning outcomes. Do the following outcome statements meet the criteria of a good learning outcome: Observable, measurable, and focus on student action? Click on the card for each outcome statement to check your answers. To have the card text read to you, simply click on the card. How do I write good learning outcomes?As you saw in the examples above, in their basic form, learning outcomes are typically structured as By the end of the course, students will be able to...[verb] + [object]. The place where learning outcomes often fall short is the verb, the action that students will do to demonstrate their learning. Often instructors use "know" and "understand;" neither of which are directly observable or measurable. Instead, consider verbs that can measure knowledge and understanding. For example, will students write, identify, or analyze something? Is it enough for students to be able to list the steps in the Krebs cycle or should they be able to describe the steps of the Krebs cycle? The decisions you make now have a significant impact throughout the rest of the course design process, so it's worthwhile to wrestle with the language to find the best verb to indicate what level of knowledge or skills you think students should have. Many faculty members start their verb search with "Bloom's Taxonomy" (which was actually written by Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, and Krathwohl). The original taxonomy from the 1950s was revised in 2001. For information on the differences between the original and the revised version, Anderson and Krathwohl - Understanding the New Version of Bloom's Taxonomy (Links to an external site.) provides a nice description. Even though most instructors focus on the cognitive domain levels (Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, Create), there is a second axis to the taxonomy - the Levels of Knowledge. These include

Iowa State University's interactive Model of Learning Objectives (Links to an external site.) provides an interactive way to look at the intersection of the Cognitive Domain Levels and the Levels of Knowledge. If you'd like to review active verbs for learning outcomes based on Bloom's Cognitive Taxonomy, Azuza Pacific University provides a list of Bloom's Cognitive Taxonomy verbs (pdf, 47k). (Links to an external site.)

In 2003, Fink (2013) developed a "Taxonomy of Significant Learning" (Links to an external site.) which he used in tandem with his backward design approach. This taxonomy integrates cognitive and affective areas and adds a metacognitive component. His 6 types of significant learning are interactive but not hierarchical and would be used selectively depending on the learning outcome desired. They are:

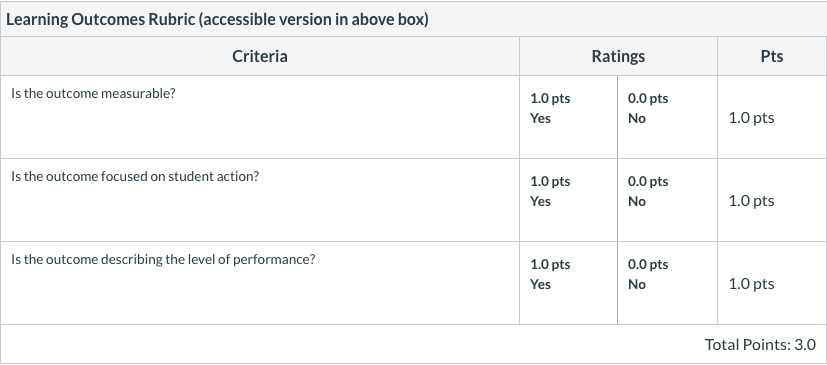

Learning Outcomes GeneratorTry composing some learning outcomes for your course with the Learning Outcomes Generator. The generator below uses both Bloom's cognitive taxonomy and Fink's Taxonomy of Significant Learning. Practice Drafting Learning OutcomesLearning outcomes express your expectations to your students and are the source of the course's structure and organization. What are your learning outcomes?This activity is a thought exercise that also allows you to see how the Blackboard Rubric tool works from a student perspective. Write at least 3 measurable learning outcomes for the course of your choice. Check them against the criteria on the rubric below. If you answer "no" to any of the rubric items you should revise your learning outcome. Write your outcomes on your course map (File can also be downloaded under Attachments at the bottom of this article), and we will return to them in the next module. Do we want to include this file? Learning Outcomes Rubric Transcript (File can also be downloaded under Attachments at the bottom of this article)

Resources for Learning Outcomes & Backward DesignAdditional InformationA Model of Learning Objectives: (Links to an external site.) Iowa State University - This includes a great interactive tool for exploring the different dimensions of the revised Bloom's Taxonomy. They also have the same content in a pdf handout (1.64MB). (Links to an external site.) Bloom's Cognitive Taxonomy is part of a set of three taxonomies (Links to an external site.) developed at the same time: cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. For outcomes in the affective domain, Bloom's co-author Krathwhol developed an affective taxonomy focusing on learning outcomes that include emotion which can influence motivation, interest, cooperation, and teamwork. The University of Connecticut provides a table of Krathwhol's taxonomy with related verbs (pdf, 18k). There are multiple versions of the psychomotor domain (Links to an external site.) which have been compiled for you to review and compare. One alternative taxonomy to Bloom is Dee Fink's Taxonomy of Significant Learning (pdf, 360k). (Links to an external site.) This is a non-hierarchical taxonomy that focuses on the interaction of 6 dimensions of significant learning. Wiggins and McTighe's (2005) backward design model "Understanding by Design" (Links to an external site.) also includes a taxonomy that integrates cognitive, affective, and metacognitive components. Their Facets of Understanding are also non-hierarchical and indicate different types of understanding. The instructor would select that appropriate facets based on the desired learning outcome. Their 6 facets are:

ReferencesBiggs, J. B. (2003). Aligning teaching for constructing learning. (pdf, 64k) (Links to an external site.)The Higher Education Academy whitepaper. Fink, D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass: Krathwol, D. A. (2002). A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: An overview Theory Into Practice, 41(4). Mercado, C. A. (2008). Readiness assessment tool for an elearning environment implementation (pdf, 99k). Fifth International Conference on eLearning for Knowledge-Based Society, Bangkok, Thailand. Suskie, L. (2004). Assessing student learning: A common sense guide Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing Company Wiggens, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design, (2nd ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

This article was:

Article ID: 578

Last updated: 29 Aug, 2025

Revision: 8

Access:

Public

Views: 6479

Attached files

|